Natty Bumppo, most likely telling the young Mohican Indian Uncas how to be a better Indian. Image found here.

Natty Bumppo, most likely telling the young Mohican Indian Uncas how to be a better Indian. Image found here.

Note: Over at my other blog, I have two brief posts on Mohicans, here and here; this one comes out of that context, but it’s not crucial to have read them before you read this one.

The frustrating (and fascinating) thing about reading The Last of the Mohicans (1826) is that, for all its insufferable didaticism it can be difficult to know whether and to what extent certain of its more intriguing textual moments are intentional. This difficulty, I would assume, is owing to what Richard Poirier succinctly describes (77) as Cooper’s lack of stylistic defensiveness. One quick example is Cooper’s rendering of Natty Bumppo’s speaking the word nature as “natur”: Apart from seeking to signify how his character is pronouncing the word, might Cooper also intend something of a more metaphysical or existential quality as regards his protagonist’s nature? I don’t know, and there is likely no way to know for sure. I mention all this because some conclusions that follow will be more speculative than interpretive; to that end, I’ll also make reference to another book, ostensibly very different from Mohicans, to provide a little support for those speculations.

Mohicans is here because of its influence on 19th-century Latin American writers who saw themselves (and their people) in the years after independence with much the same task ahead of them that Cooper’s characters face: the establishing of a new nation, and the extent to which people will shape the land, or the land them. But Mohicans is interesting to me as well because of the presence of Cora Munro, the older of Colonel Munro’s two daughters. The colonel tells Major Duncan Heyward of Cora’s origins–significantly, after the colonel assumes Heyward is interested in marrying Cora and Heyward rather awkwardly says he is not, that his interests lie with Alice, Cora’s younger, fairer, half-sister:

[Munro says, “In the West Indies,] it was my lot to form a connexion with one who in time became my wife, and the mother of Cora. She was the daughter of a gentleman of those isles, by a lady, whose misfortune it was, if you will,” said the old man, proudly, “to be descended, remotely, from that unfortunate class, who are so basely enslaved to administer to the wants of a luxurious people! Ay, sir, that is a curse entailed on Scotland, by her unnatural union with a foreign and trading people. But could I find a man among them, who would dare to reflect on my child, he should feel the weight of a father’s anger! Ha! Major Heyward, you are yourself born at the south, where the unfortunate beings are considered of a race inferior to your own. . . . [a]nd you cast it on my child as a reproach! You scorn to mingle the blood of the Heywards, with one so degraded–lovely and virtuous though she be?” fiercely demanded the jealous parent.

“Heaven protect me from a prejudice so unworthy of my reason!” returned Duncan, at the same time conscious of such a feeling, and that as deeply rooted as if it had been engrafted in his nature. “The sweetness, the beauty, the witchery of your younger daughter, Colonel Munro, might explain my motives, without imputing to me this injustice.” (151)

Heyward thus smooths things over with his future father-in-law, though not without a twinge of conscience as he feels compelled to lie to him even as he confronts a truth about himself. To his credit, up to this point in the novel he had been partial to Alice before being told of Cora’s ancestry; but now, as we see above, he has information that legitimizes to himself his not choosing Cora, even as he denies that his thinking tends in the same direction as that of the South. Heyward also provides here in miniature one of the novel’s chief themes: the tension between Reason and Nature as the deciding factor in determining our attitudes regarding race. As Heyward makes explicit in the passage above, the then-PC thing to say is that racism is antithetical to reason; yet the impulse toward racist (and racialist) attitudes seems “engrafted in . . . nature.” (Just as an aside, Thomas Dixon, in his novel The Sins of the Father (1912), will have his hero Dan Norton argue just the opposite: that racialism is a completely rational notion, and his adulterous affair with the mulatto woman Cleo is the result of his succumbing to what he characterizes as a failure of reason to control his baser impulses.)

I’ve not yet finished reading Mohicans, but thus far Cora, whose racial background satisfies the most essential prerequisites of the Tragic Mulatto–that she be darker-haired and -complected owing to some infinitesimal trace of black blood in her; that that trace render her unfit as a marriage partner–she is no tragic figure. That is most likely because she already knows the details of her parentage and, as a result, is (with the possible exception of the Chingachgook and his son Uncas) the most comfortable in her racial skin. That comfort, moreover, seems to give her a strength that Alice utterly lacks. It may also be, in part, why the attention the men show Cora is of a sort for which the best descriptor is “sexual.” In the most explicit expression of that attention, when the duplicitous Huron Magua (to whom Cooper also gives the French name Le Renard Subtil, just in case the reader needs a further marker of his duplicitous nature–there’s that word again) leeringly proposes to Cora in chapter XI that she become his wife, Cora more than holds her own. The fair-skinned and blonde Alice is also beautiful, but she is much more childlike and naïve; the attention she tends to attract is more paternalistic. It’s thus very odd to see Heyward describe Alice in the passage quoted above as possessing “witchery.” If witchery it is, it is Glinda-Good-Witch-of-the-North witchery.

Cora will not survive the end of Mohicans. As Doris Sommer argues in Foundational Fiction‘s discussion of the novel’s influence on Argentinian writer Domingo Sarmiento’s Facundo,

[Cora’s tragedy] is announced by the fact that she is the product of a leaky grid of blood. Her blood was so rich that it “seemed ready to burst its bounds” [11 in the Modern Library edition]. It stains her; makes her literally uncategorizable, that is, an epistemological error. . . . Cooper introduces these anomalous figures [Bumppo as well as Cora] as if to pledge that America can be original by providing the space for differences, variations, and crossings. But then he recoils from them, as if they were misfits, monsters. If Hawk-eye seems redeemable inside the grid of a classical reading because, unlike the gauchos, he is a man without a cross, he is finally as doomed as they are by Cooper’s obsessive social neatness. Hawk-eye disturbs the ideal hierarchies that Sarmiento and his Cooper have in mind, because neither birth nor language can measure his worth. (58-59)

Sommer’s reading here is another way of stating the terms of that tension between Reason and Nature that I mentioned earlier regarding a society’s attitudes about race. Whatever the truth of Sommer’s claim of Cooper’s “obsessive social neatness,” though, I’d argue that within the text–or more precisely, within Cooper’s characters–that debate is far from resolved, much less resolved neatly. The extent to which Cooper is actually aware of all this messiness–for which, after all, he as the author bears some responsibility–is a question Sommer, given how she characterizes Cooper seems not even to see as a question. This question of whether writers who create racially- and culturally-miscegenated characters are fully aware of how they destabilize narrative is an important one for this project.

Despite her passion, Cora exhibits a calmness: she clearly knows herself. Nowhere, thus far in the novel, does she wrestle with questions of her identity. As readers know, though, Natty Bumppo obsessively makes claims as to his “natur,” the most familiar assertion being that he is a man whose blood bears no cross. His mantra-like iteration, once we get over the impulse to mock it, becomes curious. No one in the novel questions that he is white; it is no secret that he was born of white parents but raised by Indians. Yet, if we may indulge in a bit of psychoanalysis, that constant iteration would seem to indicate that Bumppo feels a barely-subconscious anxiety about his background. Even as he expresses what can only be termed pride in his knowledge of the woods and the ways of Indians, it is as though he worries reflexively that in the eyes of other whites the very fact that he has this knowledge (or, alternately, a lack of knowledge that other whites “should” have) marks him as different in some essential way from other whites. To take only one example of this, when he initially does not properly read the tracks left by the Narraganset Bay horses that Cora and Alice are riding–a breed of horse that Cooper had earlier provided information on via a footnote for his readers’ benefit–Bumppo feels compelled to explain why he had failed: “[T]hough I am a man who has the full blood of the whites, my judgment in deer and beaver is greater than in beasts of burthen. Major Effington has many noble chargers, but I have never seen one travel after such a sideling gait!” (113) Bumppo apparently fears that someone might interpret his ignorance of one breed of horse, fairly uncommon though it is, as a sign that he is somehow less than white–hence his felt need to say that he has “the full blood of the whites.”

At the beginning of this post, I wondered whether, by rendering Bumppo’s pronunciation of the word as “natur,” Cooper might want to suggest something more existential about his protagonist: that he at some level feels some lack in his nature that puts him at risk of being alienated from the people with whom he claims a racial kinship. It’s here that I would like to engage in a bit more speculation: that the key to Bumppo’s anxiety is suggested by a pun, which may or may not be intentional on Cooper’s part, in Bumppo’s saying that his “blood bears no cross”: that is, that while Bumppo believes in God and “Providence,” it would be a mistake to identify him as a Christian–at least, as that term is understood by the other whites in the novel. At a time when religious affiliation, a community’s being held together and affirming its members via a shared faith in God–and, more precisely, a shared expression of that faith via theology and doctrine–was an accepted part of communal life and was fully embraced by almost everyone, it is not too excessive to suggest the possibility that Bumppo’s spiritual estrangement from his fellows compels him to affirm his kinship via his consanguinity–his “natur”–all the while fearing that even consanguinity might not be sufficient.

Continue reading →

Filed under: Uncategorized | 1 Comment »

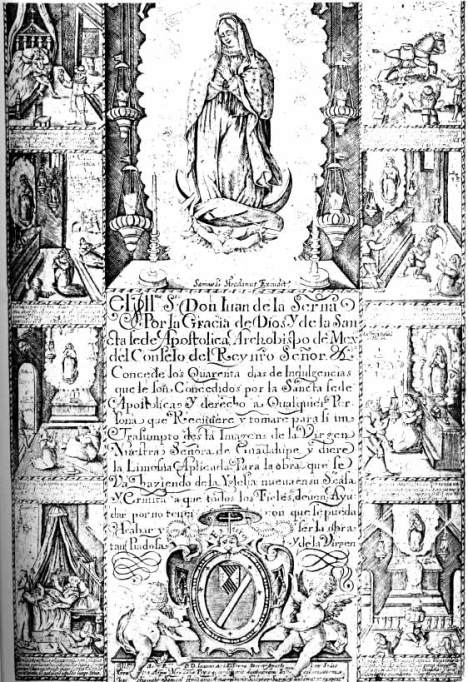

Sor María Antonia de la Purísima Concepción, 18th century, Ex Convento de Culhuacán (pictures), Mexico City. Click on the image to enlarge. The caption records her parents’ names, her birthdate, and the date and place she took the habit for the first time. As the picture indicates, by the time of its making the Virgen de Guadalupe had become an officially-approved icon for devout Catholics.

Sor María Antonia de la Purísima Concepción, 18th century, Ex Convento de Culhuacán (pictures), Mexico City. Click on the image to enlarge. The caption records her parents’ names, her birthdate, and the date and place she took the habit for the first time. As the picture indicates, by the time of its making the Virgen de Guadalupe had become an officially-approved icon for devout Catholics.

Natty Bumppo, most likely telling the young Mohican Indian Uncas how to be a better Indian. Image found

Natty Bumppo, most likely telling the young Mohican Indian Uncas how to be a better Indian. Image found  I want to return to this image for a moment, which I posted on

I want to return to this image for a moment, which I posted on